Primates, our nearest animal kin, recover three times faster than humans.

Mankind's healing process can be exceptionally sluggish compared to our primate counterparts, as per a new study published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.

Apparently, human wounds take around three times longer to heal than the same injuries in nonhuman primates, such as chimpanzees. However, this difference isn't noticeable when comparing healing rates among other species of primates or between nonhuman primates and mammals like rodents. This finding suggests that our late-blooming healing may be a product of some evolutionary shifts in our ancestry.

"The slow wound healing observed in humans is not a common characteristic among primate order and highlights the possibility of evolutionary adaptations in humans," the researchers wrote in the study.

The healing process involves several stages, starting with clotting, followed by the introduction of immune cells and a reconstruction of damaged tissue. Finally, new skin cells migrate across the wound to cover it. While other mammals heal in much the same way, some species like cats and horses use a method called wound contraction, whereby the edges of the wound are pulled together like stitches in sewing.

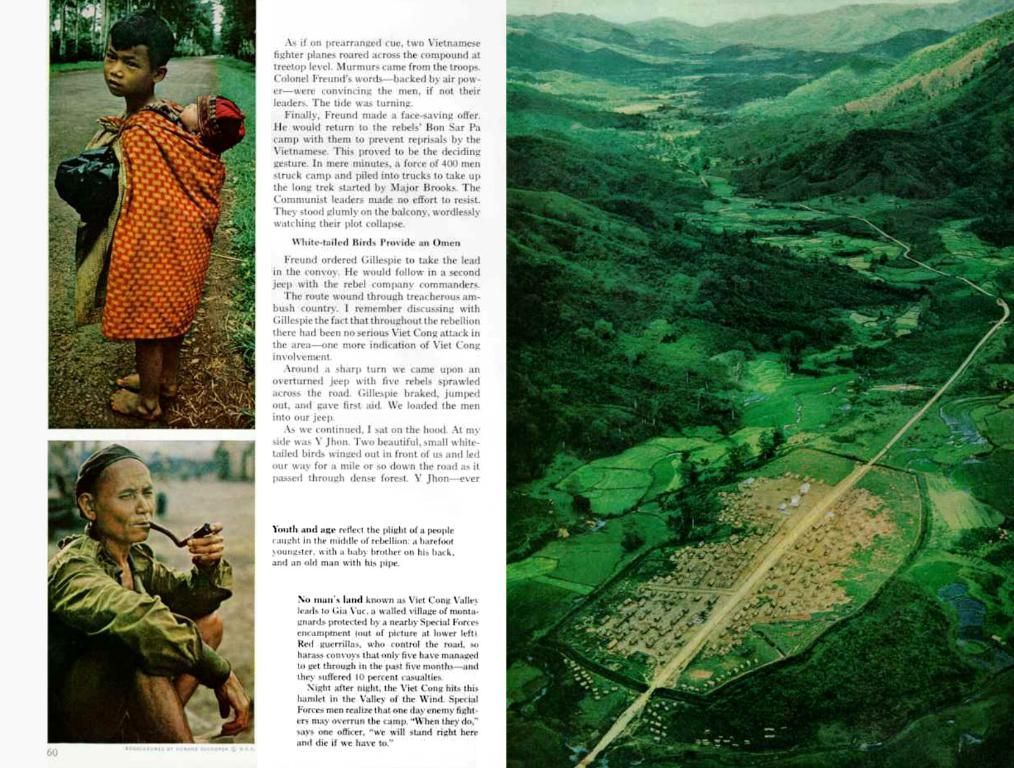

The researchers tested the healing rates in olive baboons, Sykes' monkeys, and vervet monkeys housed at the Kenya Institute of Primate Research and chimpanzees residing at the Kumamoto Sanctuary of Kyoto University in Japan, as well as rat and mouse wounds in the lab. They found that the healing rate in humans was significantly slower compared to the other tested species.

It appears that the human body has evolved slower wound healing relatively recently, likely after our last common ancestor with chimps parted ways around six million years ago. This slower speed of recovery may seem counterintuitive, as it could reduce our ability to flee from predators and scavenge food, as well as consume more energy needed for growth and reproduction.

The researchers speculate that our slower healing may be the result of our unique physical characteristics. A decrease in body hair density, which might have stemmed from a higher concentration of sweat glands, could possibly leave our skin more exposed to injury, resulting in the need for a thicker layer of skin to offer protection. This thicker skin might have contributed to slower healing rates.

Human social groups and our early forays into medicinal plants could have mitigated some of the disadvantages of slower healing, according to the researchers. Nevertheless, much research is still needed to fully comprehend the reasons behind our tardy healing.

"A more comprehensive understanding of the underlying causes of delayed wound healing in humans requires a comprehensive approach that integrates genetic, cellular, morphological, fossil human skeletal and extant non-human primate data," the researchers wrote.

🔎 Welcoming you to our daily newsletter!

Sign up now!

Join our newsletter community and be among the first to unveil the world's most captivating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox every day! 🛰️🌟

🎯 Fun fact:

Human ancestors mostly had twins – unlike us humans today – thanks to an evolutionary reason!

📚 Shedding some light:

- Understanding the physiological and evolutionary reasons why humans don't go through menopause like chimps could reveal fascinating insights.

- The primate ancestor of all humans likely walked alongside dinosaurs millions of years ago.

🤓 Tidbits from the enrichment data:

👨

- The study highlights that human healing processes, particularly when it comes to wound healing, may be influenced by evolutionary adaptations, making our healing slower compared to other primates.

- Mental health, fitness, and skin care are important aspects of health and wellness that require attention and therapies and treatments, separate from the evolutionary adaptations impacting physical healing rates.

- The researchers' comprehensive approach to understanding human healing involves integrating genetic, cellular, morphological, fossil human skeletal, and extant non-human primate data, indicating the multidisciplinary nature of the study.