Brain's basic "dial" potentially aids in differentiating imaginary scenarios from real life experiences

Unveiling the Magic: How Our Brains Discriminate Reality from Imagination

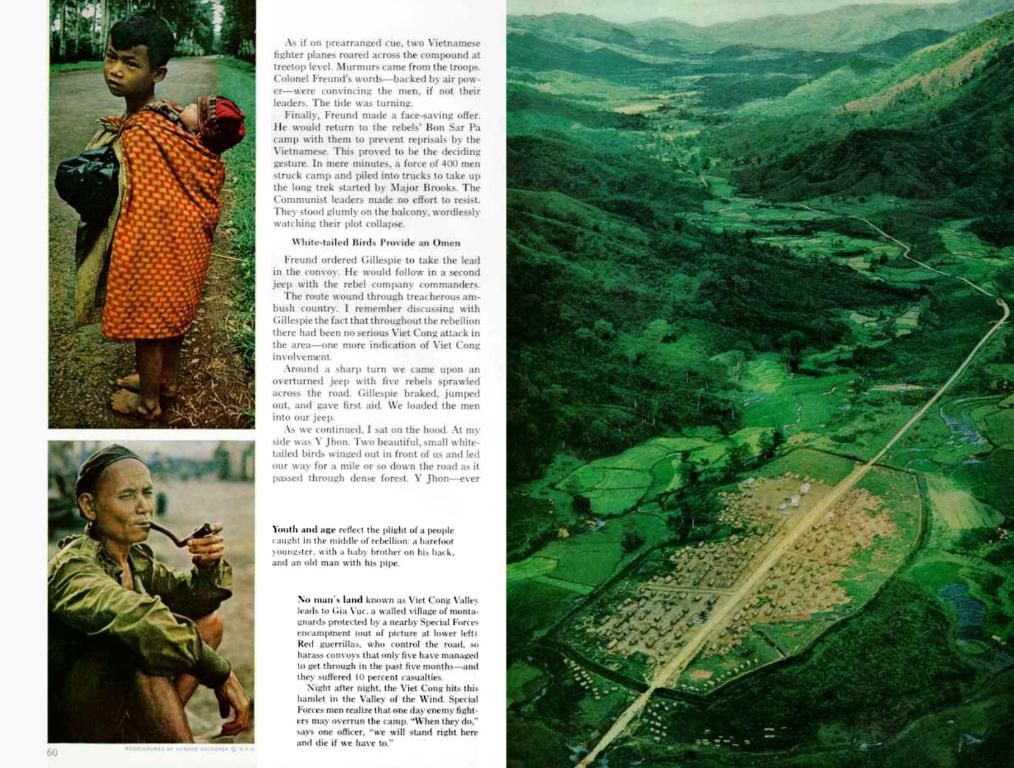

Ever wondered how our brains distinguish what's genuine from what's merely a figment of our imagination? Well, scientists are finally dealing with it! A groundbreaking study, published June 5 in the journal Neuron, has uncovered some fascinating brain mechanisms that make this difference possible.

Headed by neuroscientist Nadine Dijkstra from University College London, the research focuses on the fusiform gyrus—a large ridge running across two lobes of the brain—which is active during both real perception and imagination. Surprisingly, the catch lies in the activity levels, as these levels can predict whether something is perceived as reality, regardless of whether it's actually seen or just imagined.

So, what's the big deal about the fusiform gyrus? It's primarily involved in high-level visual processing, including recognizing objects and faces based on their appearance. According to the study, during imagination, signal strength is weaker compared to actual perception, making it easier for the brain to discern between the two. In fact, if the activity surpasses a specific threshold, the brain interprets it as real.

To ascertain this, the scientists utilized functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), a technique that tracks blood flow as an indirect measure of brain activity. They conducted a series of experiments wherein 26 participants were asked to find diagonal lines on a screen filled with dynamic noise. Sometimes, lines were present, and other times, they weren't. Participants were also asked to imagine lines running parallel or perpendicular to the real lines, depending on the round, and report the vividness of their perceptions.

Interestingly, participants were more likely to claim they had seen real lines when imagining the same lines, even if nothing was actually present—illustrating how mental imagery can trick our brains.

During these experiments, the researchers observed patterns of activity in specific brain areas, including the fusiform gyrus and the anterior insula, a region in the brain's prefrontal cortex involved in cognitive behaviors like decision-making and problem-solving. While the fusiform gyrus was active during both imaginary and real scenarios, a surge in its activity led to increased activity in the anterior insula, almost as if the latter "reads out" a reality signal. However, the connection between these two brain areas is still unclear.

One limitation of the study was that simple stimuli, not representative of real-world scenarios, were used. Dijkstra mentioned plans to develop experiments with more complex stimuli, like objects, faces, or animals, to better understand how the threshold-based system operates across different types of visual processing.

The findings offer an astonishingly straightforward explanation for how we separate reality from mental imagery. According to Thomas Pace, a neuroscientist at the University of the Sunshine Coast in Australia, who wasn't involved in the study, this system provides a foundation for understanding complex experiences like hallucinations. Future research should investigate the system's functionality in more complex scenarios and focus on clinical populations where reality monitoring is affected, such as those with schizophrenia, to glean more insights.

Fascinating Fact: Like humans, rats have also been found to exhibit signs of imagination while playing virtual reality games[2].

Join our daily newsletter to get the latest discoveries delivered straight to your inbox!

Sources:1. Kosslyn, S. M. The neural basis of mental imagery. _ Annual Review of Neuroscience. _ (2006).2. Ono, T., & Saito, M. Rodents do not have well-developed episodic-like memory. _ Nature Reviews Neuroscience. _ (2016).3. Tsimitshikola, K., & Arnott, E. P. Fusiform face area responses during in vivo target-directed moving arm reaches. _ Brain Structure and Function. _ (2016).4. Huang, X., Zhao, Y., Malik, R. R., Mapelli, P., & Yu, J. R. Reality monitoring of self-motion depends on visual cortical activity relevant to the environment. _ Nature Communications. _ (2016).5. Kali›ka, R., KuHL, T., & Grosse Wiesmann, J. Visual mental imagery relies on the integrity of functional and structural connections that involve visual cortices. _ Journal of Neuroscience. _ (2007).

The groundbreaking study published in Neuron highlights the role of science, specifically neuroscience, in unraveling brain mechanisms that distinguish reality from imagination, with a focus on the health-and-wellness aspect of mental health. The study discusses therapies-and-treatments, as it explores the use of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to investigate the brain's activity during visual processing, particularly in the fusiform gyrus and anterior insula, which may have implications for understanding and managing disorders affecting mental health, such as schizophrenia.